An Introduction from the Editor

Welcome to the 21st edition of the Wyvern Newsletter. This issue brings together stories that capture the spirit of Stanbridge—adventure, friendship, and the kind of mischief that only makes sense in hindsight. From Hugo Sanders’ tribute to Felix to Douglas Home’s 1962 sailing account, these stories show just how vividly Stanbridge still lives in its people.

You’ll also hear from Andy Philpot on life with Dick and Erica Gould, and from Bernard Acworth on his time in Mr Abraham’s House. Alongside these are reunion photos and reflections from across the decades—each voice adding to the story of a place that was, by turns, rigorous, eccentric, and unforgettable.

We’ve just completed a project uploading all of Martin Milward’s previous editions as PDFs to our Substack, so you now have easy access to every edition

For our next project, we’re looking to collect whole-school and staff photos from every decade. If you have any, we'd absolutely love to receive them. We already have several from the 80s, 90s, and 2000s—and once we have them all together, we’ll focus on identifying the exact years. If you have a photo, you’re welcome to email it. Or post it to us—we’ll scan and return it safely.

Enjoy the issue—and please share it with Wyverns everywhere!

All the best, Ben.

From the Chairman's Desk

by Peter Bragg, 1960-1964

I hope you are all keeping well.

I continue to visit the school premises on a regular basis. It is always enjoyable to walk around the grounds. Of course, it is not the same. The games field, once flat and well looked after, is no longer flat. It is dome-shaped because the rubble from the demolition of many school buildings and staff houses was dumped there to save costs. Audley has now spread topsoil over the rubble and has sown grass seed on top. The long-term plan is to landscape the area so that it looks like a meadow, allowing residents to walk around it with their dogs. The three lakes remain untouched and will always look familiar.

Earlier this month, we had the first of our reunion lunches at Audley Stanbridge Earls. It was attended by 21 Wyverns from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. We sat in the main dining room and enjoyed excellent food and good service from the staff. After lunch, there was a short tour of the main school house and grounds, as some Wyverns were visiting for the first time since the major changes. Martin Milward is writing about this event in this newsletter.

As we are finding it difficult to agree terms with London venues for our traditional reunions in the city, we will be organising another get-together at Stanbridge in August 2025 to celebrate the 'Good Days' at the school. This time it will be a lunchtime barbecue. Details are included in this newsletter. I hope 25 Wyverns and members of staff will be able to come.

Best wishes to all,

Peter Bragg

Join us at the Wyvern Reunion Barbecue: “The Good Days at Stanbridge”

Saturday 2nd August 2025 at 12:00 pm.

Following the success of the first Wyvern Reunion Lunch held in May 2025, we are organising a second reunion at Audley Stanbridge Earls, by way of a lunchtime barbecue, to celebrate “The Good Days at Stanbridge”. We hope to take advantage of sunny weather and sit outside, but in the event of rain, there is a contingency plan to relocate inside.

There is a small cost of £30.00 per person, and the Wyvern Society will provide the wine. It would be particularly good to see Wyverns from the 1970s and 1980s, and former members of staff who contributed to “The Good Days”. We hope to gather at least 25 Wyverns for the event.

We look forward to seeing you there!

Further details will be provided nearer to August. If you would like to attend, please let Peter Bragg know by email: pejbragg@btinternet.com

Wyvern Society Reunion Lunch – May 2025

21 Wyverns from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s

By Martin Milward (D, 1973)

In the first of a new series of reunions, 21 Wyverns from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s gathered for lunch at Audley Stanbridge Earls on Saturday, 17th May. After a welcome drink in Oak Hall, we moved to the Dining Room—a space many of us fondly remember as the Chapel—for a delicious three-course lunch in comfortable and familiar surroundings.

Convivial conversations and amusing reminiscences about the ‘good old days’, now so long ago, made for a wonderful gathering enjoyed by all. The hospitable and attentive staff then gave us a tour of the Main House, now tastefully redeveloped into high-end retirement accommodation, and the beautifully landscaped grounds with smart apartments in place of former huts and classrooms.

A personal highlight was revisiting a first-floor, front-facing room in the Main House, once known as "Hutchinson". This was my dormitory during my first term in 1967. As a new boy, I hadn’t appreciated the beauty of its oak beams, intricate panelling, and the family crest above the fireplace—but I clearly remembered the smelly socks and late-night chatter after ‘lights out’!

Beautiful summer weather enhanced the reunion, allowing us time on the patio behind the Main House, chatting with residents and strolling over the expansive lawns to the Middle and Bottom Lakes. We saw geese—safe now, free from the dubious attentions of mischievous schoolboys!

It was an excellent, vivid, and memorable day. Special thanks go to Wyvern Chairman Peter Bragg for organising this reunion.

I'd like to mark this inaugural event by listing the attendees: Peter Bragg, David Burkinshaw, Andrew Calvocoressi, Ian Canham, Robin Carpenter-Turner, John Chichester, Robin Davison, Alun Griffiths, Thomas Hooper, Richard Johnston, Mark Lowe, Mark Mendoza, Martin Milward, Hallam Murray, Colin O’Brien, Julia Parker, Michael Piercy, Julie Sewell, Michael Towers, Misha Williams, and Timothy Salter.

The school may have closed, but the Society lives on!

RSVP Book Launch Event

Andrew launches his autobiography, Potage de ma vie, on Friday, 18th July 2025, at St Ethelrida’s Church Hall (Upstairs), Fulham Palace Road, London SW6, from 5:30 to 8:30 pm.

For many years, friends and family have been encouraging me to put to paper my life story - one of adventure, triumph and disaster, international cuisine (including cooking for everyone from the late Queen to the homeless), roaming North America and Europe, particularly France and Italy along the way finding out about people, places, cuisines and most of all myself! This is my story!

Potage de Ma Vie

This is my book. Through food, people and places, I have tried to capture my journey. It has taken me 15 years to write but during that time I have actually had two of the best jobs in the world - one involved cooking for the homeless - the other for a classical musicians seminar in Cornwall. These and many others made me the person I am, although I knew from an early age that I had a different connection with people irrespective of their background or circumstances.

Andrew’s book is scheduled for publication in late July 2025.

For further details and to RSVP:

Visit: calvos-cuisine.com

Contact Andrew directly: calvo3@hotmail.co.uk

FELIX

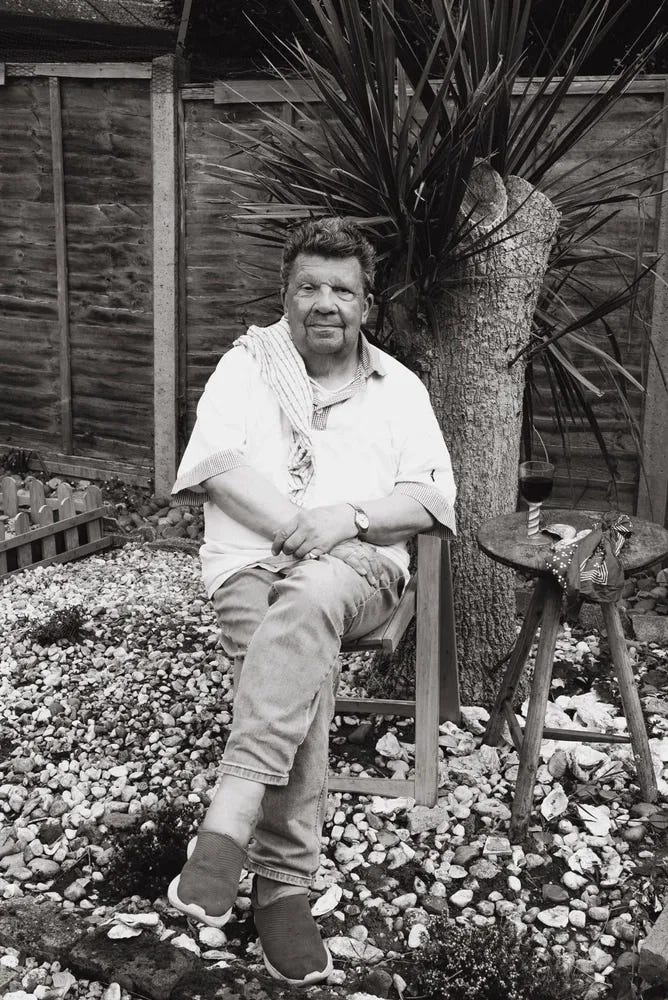

by Hugo Sanders, 1971-1974

I first met Felix at Stanbridge, way back in the early ’70s. Before his arrival, like any bunch of adolescents left to their own devices—sparing the gory details—life was a bit like Lord of the Flies. Then along came Felix: 6’3”, bright blue eyes, and a deep shock of red hair. He was like a bird of paradise, blown off course and dropped onto our rain-sodden doorstep.

Felix wasn’t into Lord of the Flies; Felix was into fun. He possessed that rare quality known as PMA—positive mental attitude. He was always unfailingly cheerful and polite, no matter what. He was the kind of bloke you’d like to share a trench with. He never complained. He was always... just Felix. What’s more, he was hilariously funny. To spend the day with Felix meant your sides were splitting with laughter from morning till night. It was agony.

When Felix landed on us, the whole school was transformed into a happier and more cheerful place. His instinctive kindness, humour, and sensitivity permeated every corner of the school. It was infectious. Soon, we were all at it. During fag breaks by the school lake, he would regale us with stories of his life in London, with his sisters (whom he adored), and about his elaborate schemes to get rich quick and the practical jokes he was planning to hatch.

So it came to pass that Felix, Willie—another great friend—and I became inseparable. He introduced a level of sophistication previously unknown to us. His conversations were about rare breeds of cat, the Beat poets of the ’50s, and famous Italian film directors. This was a revelation to me—I was still reading The Beano!

When we occasionally sneaked off to the pub, Willie and I sat nursing half-pints of mild and sharing a pack of crisps. Felix, meanwhile, would sip a double snowball—ice and a glacé cherry—while puffing away on a Balkan Sobranie cigarette. In our less dignified moments, we’d turn the record player up full blast after homework and play air guitar to Bachman-Turner Overdrive until it was time for bed.

Felix had a precocious talent for business. In the school grounds was a huge old dilapidated Burmese temple, slowly rotting back to soil in the persistent rain. He had his eye on it for months. He picked his moment, approached the head, made a sensible offer, arranged transport to London—and sold it to a high-end restaurant, where it probably remains to this day.

Ben-Hur

That same year, on the last day of summer term, we were enjoying a crafty smoke where the temple once stood. The groundsman had left his handcart nearby. It was Sports Day. A light summer breeze blew across the manicured lawns. Smart-looking parents were being gently wafted along by smiling, attentive masters.

We eyeballed each other. We didn’t have to speak—we just knew.

“This’ll mean a flogging. Six of the best?” I said.

“Not six—possibly four,” replied Willie.

Whatever the consequences, we were going in. We stripped stark naked. Willie climbed onto the cart. Felix and I took the handles. All set, we pushed the cart as hard as we could towards parents and masters.

Willie was now Ben-Hur at the Circus Maximus. The cart was his chariot. Felix and I were his spirited stallions. Cracking his whip, he goaded us on.

As we passed the chapel once frequented by Ethelred the Unready, Mr Raymond—our beloved French master—was laughing his head off and quickly ushering parents through a stone door. Others scattered to the safety of the marquee.

At the far end of the main building, we reached a quandary. Our clothes were 150 yards away. We had no choice. We turned around and charged back as noisily as we could. Back at the temple site, we collapsed in laughter. When we looked over to the school, it was like the Mary Celeste—not a sign of anybody.

To the school’s enormous credit—and our grateful relief—there were no repercussions. Not even a bollocking. Not even a mention. It was our finest hour.

Life was not always easy for Felix. On the occasion of his mother’s death, he bore the news with unfailing dignity and restraint—far beyond his tender years. Eventually, the time came to leave school. Felix went to North Wales. The Charltons had kindly offered him a place to live and work at Celmi. So far, so good—but in short, we were now adults with the freedom to do exactly as we pleased, and a whole carpet of temptations, mostly of the liquid kind, lay before us.

Two years later, Felix returned to London and became involved with the early punk scene. He worked on building sites and as a barman at the Chelsea Arts Club. The bar work meant he rubbed shoulders with some fascinating and well-known characters. With his easy charm and shock of red hair, the Irish navvies took him as their own and whisked him off to the pub at every opportunity.

Felix’s get-rich schemes and practical jokes became even braver and more audacious.

The Chelsea Rug Store Heist

Back at school, during the holidays, Felix managed to secure employment at the Chelsea Rug Store on the King’s Road. These were high-end, hand-woven rugs imported from all over the world—some of them worth a king’s ransom. Around the same time, a friend approached him saying he had three quite nice rugs and wondered whether Felix’s boss might want to buy them. The boss inspected them, said they were indeed of good quality, but couldn’t buy them himself—though he’d try to find a willing customer. That was the last the friend saw of his rugs, or of any money he was owed. Felix was genuinely outraged. When he wasn’t ranting about it, it gnawed away at him. It wouldn’t go away—until a plan was hatched and karma dispensed, once and for all.

As it happened, an opportunity arose quite soon. The owners were converting half the shop into a restaurant. Builders were currently working on the WC, and while everyone was away at lunch, Felix carefully lifted three of the most expensive rugs from the rack and discreetly stashed them behind the WC cistern. When the builders returned, he watched quietly as they panelled over the cavity—rugs sealed inside, ready for phase two.

Years later, Felix returned from Wales. The time was right. We met at The Roebuck, on the King’s Road, for drinks and a council of war. The usual crowd of punk rockers were nursing their cokes, wearing chrome-studded jackets, safety pins, and purple Mohicans. They didn’t chat—punks rarely do—but we enjoyed a few games of pool together. As the evening wore on, we became as drunk as skunks. I remember Felix having to hold me over the pool table just so I could take my shot. The punks won.

All of a sudden it was 9pm. We left our ninth pint on the bar—time to focus. We swerved down the street to the rug shop–restaurant. They were offering nouvelle cuisine. It was my job to liaise with the maître d’. I was desperately trying not to slur my words: “We’ve heard encouraging news of your establishment and are keen to sample your wares,” I announced in a loud voice. Felix was behind me, silently looming, swaying slightly. He was wearing a dark hoodie and jogging bottoms, and carried a huge canvas bag clanking with tools. He couldn’t resist dressing the part. Nevertheless, the maître d’ showed us to a table.

It was a quiet night. We ordered, and the hors d’oeuvres arrived. Then Felix rose to his feet, picked up his bag, and made for the loo. Twenty minutes later, the main course arrived—but no Felix. Another twenty passed. Still nothing. I made my way to the gents to see what the holdup was. The place resembled a disaster zone. A huge jet of water was spouting from the wall and we were both ankle-deep in it. In his effort to reach the hidden rugs, Felix had ruptured the water supply pipe. He was soaking wet from head to toe, with a desperate look in his eyes.

I returned to my seat, buried my head in my hands, and wished it would all just go away. Eventually, Felix emerged. “I feel sick!” he shouted abruptly, then bolted out the door—carrying a bag full of priceless Persian rugs. The staff were politely concerned about my friend’s wellbeing—so was I. I made our apologies, vowed to return once he’d recovered, and slipped out before they noticed the flood now streaming into the dining area.

Felix didn’t get much for the rugs. They may have been worth £800 apiece in Chelsea, but the folk at Portobello Market just wanted something to wipe their feet on. What little he made, he gallantly handed over to his friend.

The Minibus Tour Scheme

The plan was to buy a worn-out old minibus for a pittance, find paying passengers, and schedule a trip to Aberdeen. Obviously, it would break down within two miles of London and have to be towed the rest of the way to Scotland—courtesy of the RAC, absolutely free of charge. Luckily, the scheme broke down before we could even arrange suitable transport.

Uggy’s Morris Minor

Felix wanted to play a practical joke on his old friend Uggy. The idea was to hitchhike to North Wales, steal Uggy’s Morris Minor, and drive it back to London—then phone him to say where it was. Hilarious. The fact that neither of us could drive, and that Felix already had a five-year ban, was irrelevant. I was definitely up for it. Off we went, thumbs out at the Hammersmith Flyover at 8am sharp. What could possibly go wrong?

After walking for miles in the middle of nowhere, we eventually reached our destination at 2am. We approached the shed where Uggy kept his Moggy. Slowly, we opened the creaking door and wheeled our prize silently down the steep track to the road. We climbed into the front seats. Felix turned the ignition... Nothing. Again... nothing. A third time... still nothing. Puzzled, we lifted the bonnet.

A huge dark void stared back at us. Uggy had removed the engine. There was no alternative but to return to London immediately. We limped back over the Hammersmith Flyover, exhausted—barely able to place one foot in front of the other, having unsuccessfully slept under a hedge near Newbury.

Felix’s sisters were not pleased. They knew we were up to no good. When we recovered, there was a post-mortem. Quite frankly, we felt pretty silly. We were being hindrances to people who had their shoulders diligently to the wheel, trying to earn an honest crust. They were forging a life; we were creating a distraction.

It finally occurred to us that quietly getting on with life was actually what it was all about. Felix really took this to heart and vowed never to touch a drop of alcohol again. He was 21. When we met again, 14 years later, Felix was no longer working on building sites or in bars. He was now an IT consultant. Living alone, he was breeding rare Persian cats which padded about like silent, white fluffy clouds through his lounge and out into the small sculptured yard at the rear. The place was filled with wonderful antiques. "Aha!" I thought, "Felix has made it." He had recently converted to the Catholic faith and was volunteering for the AA, urgently attending to anyone in need—day or night—at the drop of a hat. After 45 minutes, he announced he had pressing work to do in his office that wouldn’t wait until Monday. "Fair enough," I thought. "If you want to get ahead, you have to make sacrifices." I had to laugh though—I noticed he had spent so much time in the gym that he couldn’t even get through the kitchen door unless he went sideways!

It was a full 23 years before Felix and I met again, at a reunion dinner arranged by Willie. This time, he was back to his old self. He was no longer in IT and was now a fully trained actor—and adoring it. Charming and witty, his blue eyes were sparkling once more. He was full of plans and schemes for the future. However, he no longer looked at the peak of his physical condition. "Oh well," I said to myself, "actors do struggle to keep body and soul together," and thought no more of it.

Once again, life took over. Another nine years passed. I emailed him as a school friend was terminally ill and wanted to contact him. "I will do that right away," he replied. Little did I know that Felix had contracted cancer of the spine and had only a few months left to live.

The sufferings of death are something we must all endure, but what affected Felix the most was losing his sight. Yet he never lost his thirst for knowledge. "Of course I’m frightened," he told friends, "but I’m curious as well."

And so we buried him, that great, lanky bird of paradise who, blown off course, landed on our rain-sodden doorstep all those years ago. "Hail Felix!" somebody cried as they lowered his coffin into the ground. We chuckled about this as we strolled to the wake. "Felix would have loved that," I said—to which all agreed.

Felix touched many people’s lives. When he wasn’t being charming and entertaining, he was discreetly and conscientiously helping others. He was hilariously funny, great fun, and kind. Above all, he was generous—not only with his possessions (which he was, to a fault), but with his time. And that, as we can all appreciate today, is the most precious commodity on earth.

He really was one of the very, very best. Goodnight, my old friend—and God bless.

A selection of some of Felix’s stage characters can be found below…

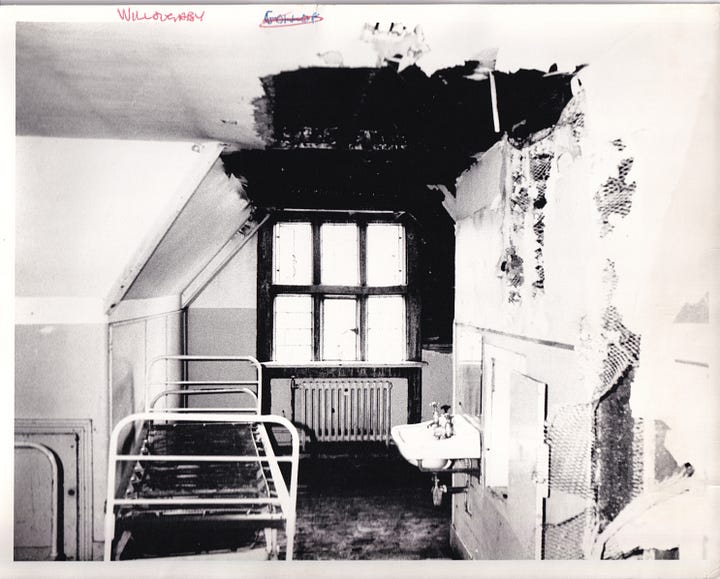

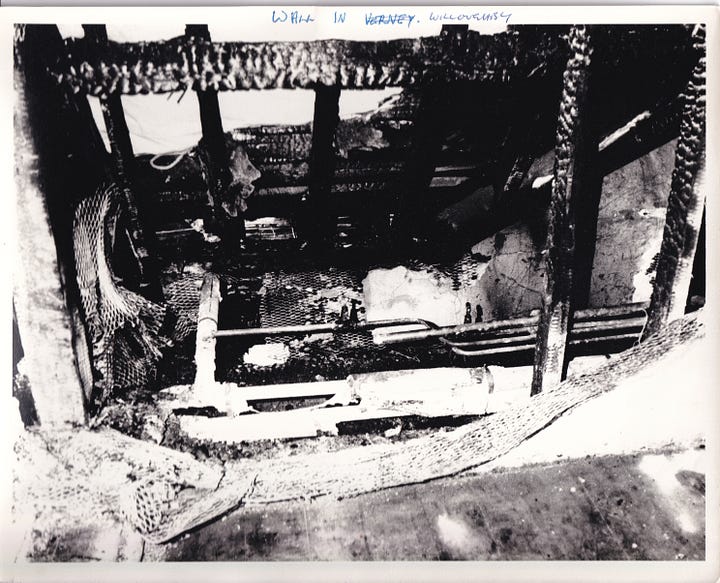

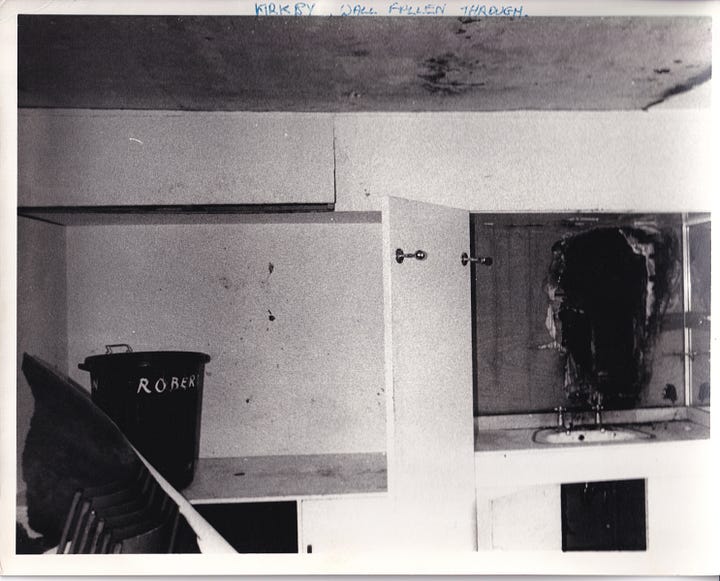

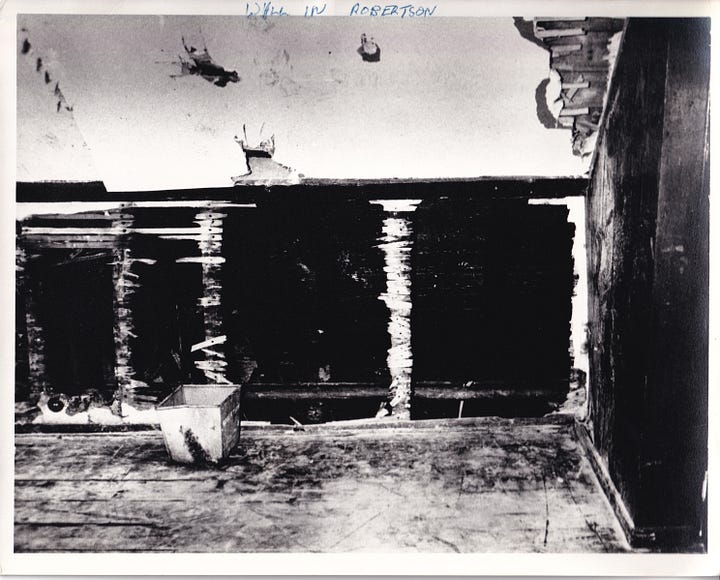

The Fire

Request: We have some intriguing photos of a fire at Stanbridge, and we believe it might have happened sometime in the 1970s. If you were there, we’d love to hear your account—what exactly happened, what might have caused it, and any memories or details you can share. Your stories help fill in the gaps of our shared history!

My Life with Dick and Erica

by Andy Philpot

I first met Dick and Erica when they arrived in Oxford after the war. Dick was taking up a place at Christ Church College and I was a young boy of three or four. We lived in the top flat of an old Victorian house in North Oxford, and Dick and Erica moved into the flat below us.

Life with Dick and Erica was never dull. One Sunday morning, they went off to church, leaving the Sunday roast in the oven. When they returned, they found they had left their keys inside the flat. So, my father climbed up and in through their loo window, saving the day—and the roast. My father was a rock climber and, being a Victorian house, the plumbing was conveniently on the outside. My mother kept him safe with a rope out of our loo window.

On another occasion, my mum heard hammering coming from the stairway between our flats and found Dick trying to break the window in their front door with his shoe. They had gone to the theatre and left their tickets behind. When Dick got home, he realised he’d also left their house key at the theatre—with Erica. Without saying a word, Mum returned to our flat, got a hammer, and handed it to Dick.

Dick and Erica’s furnished flat came with a large painting of Queen Victoria. When they moved in, they replaced her with an equally large picture of the Dalai Lama. (Dick spent his childhood in northern India and Afghanistan.) However, when the landlady came on her annual inspection tour, Dad had to be called in to help Dick put the Queen back in place and move the Dalai Lama into safe keeping with us for the duration. And oh, that wonderful day when Dick brought home an old Rolls-Royce!

In early 1962, I obtained a place at Sussex University, and my wise mother thought it was a waste of time to stay in school for the rest of the academic year. She contacted Dick at Stanbridge and asked if he could use my services. He said he could, and I was put on a train to Romsey. As David Pearse occupied the only staff bedroom in the school, I was installed in a small green caravan over by the tennis courts—which suited me perfectly.

On my first morning, while walking over to the school for breakfast, I heard a cheerful voice behind me say, "Good morning, sir." I looked around to see who the students were talking to and realised it was me. Although nineteen and still pretty wet behind the ears, I was treated like a full member of staff and had all the duties—except for teaching. But I was far from idle.

My jobs at Stanbridge were diverse. I tutored in maths and English, mowed the school field, marked out the athletics track, kept the swimming pool filled and clean, drove students out into the New Forest in search of badgers, and did anything else that needed doing but nobody else wanted to do. I was never bored. In my spare time, I played lots of tennis with the matrons—Claire Woods and Sandy Wilson—and with Erica when she needed an opponent or a partner.

At one point, I was told to drive some large wooden stages for a school service at the Abbey. I was to use the school tractor and trailer. Never having driven a tractor before—apart from in circles on the school field—driving into town with a trailer was nerve-racking. But I made it there and back without incident. I was then coerced into reading a lesson at the service—a little more intimidating than reading one in my school chapel as a prefect.

One day at lunch, we had rice pudding—something I hate. So I dished it to the boys at my table but didn’t take any for myself. After the meal, I was cornered by Erica and told that I was expected to set an example and eat whatever was put in front of me.

But my favourite duty, if you can call it that, was taking a group down every week to go sailing on the Hamble River. The school owned a 16' Wayfarer dinghy and two 12' Fireflies. This was fun—until Dick suggested we sail across to Cowes, where he would buy us lunch at the Royal Yacht Squadron. I had grown up sailing on the Thames in Oxford, so crossing the Solent was a bit of a challenge and, in retrospect, something I probably should never have undertaken—a seven-mile trip of open water with three dinghies and seven boys. Luck and a fair wind were on our side and we arrived in Cowes in time for lunch, despite being completely becalmed at times by passing ships entering Southampton Water. We made it back as well, but I still shudder when I think of all the disasters that might have befallen us.

I should like to thank all of the staff at Stanbridge at that time, as they welcomed this young kid just out of high school and treated him like an equal. But in particular, I have to thank John and Marjorie Abraham, who adopted me and gave me a wonderful home away from home during my time at Stanbridge. Well—not quite home, as I had to return to my caravan every night.

I still have a book, The History of the Boat Race, presented to me when I left. When I look at the names of all the staff who signed it, many happy memories come flooding back.

And then it all came to an end. My time at Stanbridge had been wonderful, and I was a much more confident person due to the responsibilities that Dick had thrust upon me. Some years later, the Stanbridge experience led me into a thirty-year career in teaching—first in Nigeria and Zambia, and then at Hillfield-Strathallan College, a private school here in Canada—retiring in 1999. It also made me a firm believer in the importance of gap years.

After Dick retired, he became involved with promoting gap years and came to Canada to drum up some enthusiasm. He stayed with us after visiting Ottawa to see whether the government would support the idea—but had met with little encouragement. He then came down to visit us in Hamilton while touring several private schools in the area—again with little success. To cheer him up, we took him to Niagara Falls for the day. (Bucking the trend, my wife Anne and I sent both our daughters to England for their gap years as matrons in two prep schools in Oxford.)

But we weren’t finished with Dick and Erica. We have friends in the New Forest, so visits to Lymington were always in order whenever we were in the neighbourhood.

On my last visit for dinner, Erica finally left Dick and me talking long into the night—about rowing, education, and of course, Stanbridge.

1969 Entry Reunion

The Duke of Wellington, London (September 2024)

Organised by Riou Baxter, this photo captures members of the 1969 SES entry group—Bevan, Baxter, Balchin, Avison, and others—gathered for one of their regular five-year reunions. Pictured around the table: Webster, Gascoigne, Robinson, Chris Butler, Milward, Panayi, Milton, Macnab, Bevan, Baxter, Balchin, Avison, and Clauson.

Others who hoped to attend but couldn’t: Geddes, Bigge, Beal, Rouse, Meaby, and Mike Butler.

We also remember with affection those no longer with us:

Philip Harris, who ran a Thai restaurant in Soho and was killed in a motorbike accident in Bangkok

Stephen Lawrence, a successful photographer who died in a hotel in Manchester

Richard Gammon ("Maggot"), who ran garage businesses in Petersfield and died after a fall

Timothy Walker, who died of cancer

James Beecheno, who passed away from cancer in Australia in June 2023

Our thanks to Riou for sharing the photos and helping keep this tradition—and these friendships—alive.

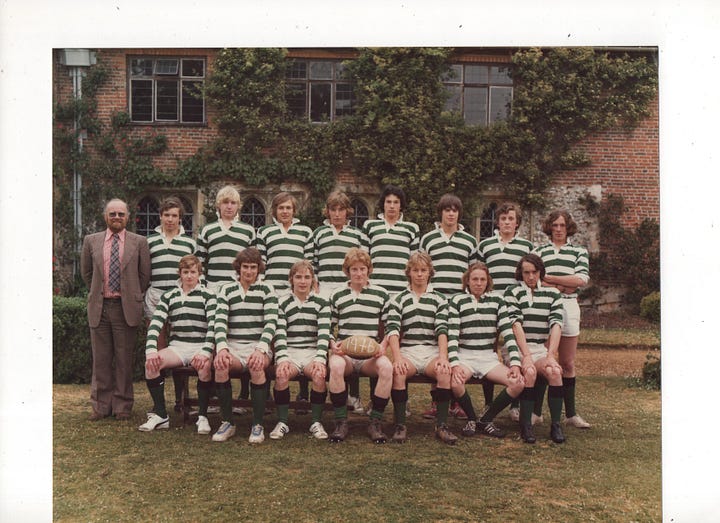

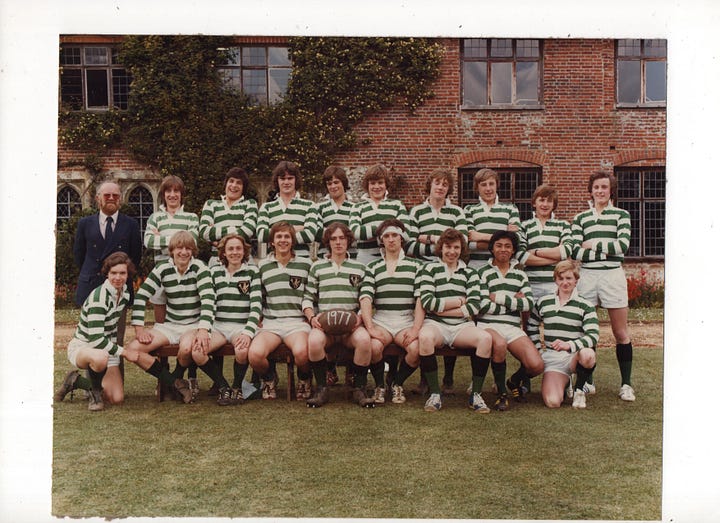

Stanbridge Snapshots: Johnny’s 1970s Photos

These photos from the mid-1970s were kindly shared by Johnny, who appears front left in the 1976 rugby team. He hopes to send more in due course. Our thanks to him for capturing moments that bring Stanbridge’s spirit back to life.

Memories of Stanbridge Earls

By Bernard Acworth

Hello, I attended Stanbridge Earls between 1959 and 1962—the year a new headmaster was appointed, Richard Gould. I was in Mr Abraham’s House.

We had early morning runs with cold showers afterwards, before breakfast, which I must admit was not my favourite time. I think my favourite lesson was woodworking. (I'm the tall one at the back of the photo.)

I took minor roles in some of the school plays. I did well at some of the athletic events—shot put, javelin, and high jump. However, I enjoyed my time there and made several good friends.

We did some of the school grounds maintenance ourselves, as shown in the pictures attached.

When I left, I continued to study at college in Brighton and subsequently joined the Metropolitan Police at 16 as a police cadet, then at 19 as a constable, where I served for 32 years.

After retiring from the police, I had various jobs before finally retiring to Hampshire, quite near to the old school. (63 years later, the road sign directing you to Stanbridge Earls School is still there!)

I still follow the news of the Wyvern Society with interest to see how the old place developed and the subsequent demise (which was most unfortunate).

I regularly attended the reunions in the past, but sadly, some of the pupils I knew are no longer with us or are unable to attend.

I have attached some photos which may or may not be of use to you. Please feel free to publish them or not, as you wish. I do have school photos from that era if they are of interest.

Sailing 1962 - Memories of Stanbridge Earls

By Douglas Home

The following account is given by Douglas Home, one of the first masters appointed by Richard Gould in 1959, who started and built up the Stanbridge Earls Sailing Club. The following episode took place in 1962.

“You must picture us rigging our boats, checking the gear and launching as smartly as we can. It is high water and there is a light south-westerly wind in our faces as we beat out of the river: it looks a good training day.

In the Wayfarer we pass the others near the river mouth and turn up Southampton Water on a close reach. Munro is at the helm and, as it is a nice gentle day, he soon hands over to one of our new members: Sedgwick.

Soon the wind grows stronger. Munro takes the tiller again and in a few moments we are planing along on two enormous bow waves which drench Liddell, who is sitting forward. We enjoy this wonderful sensation—the planing I mean, not the soaking—until my conscience smites me and I turn to look for the others. They are not in sight. The whole sky to the eastward is dark and lowering, and a rain squall has blotted out the sea astern of us.

Round we come and go sloshing back, really moving now with the wind on the quarter. There they are: four dark shapes with their sails showing brilliantly against the sombre background, and one other with no sail. Capsized? Dismasted? As we come up, we piece together what has happened. There has been a collision; one boat has lowered its mast and another is making for the shore.

Here comes the Gull, with Whitehead and Hayes sitting out to keep her upright. ‘We’ve been holed,’ they shout. We can see a small hole above the waterline on the windward side. ‘All right, get back on the river,’ we yell back. Ahead of us, Torrens’s Firefly is standing by the dismasted Mole. Mole is draped with gear—sails, mast, boom, gaff—all over the place, and Davidson and Northern are working to clear up the mess. Explanations can wait until later; the main thing now is to get Mole back into shelter (actually, the crew had lowered everything in an unnecessarily drastic emergency action). As we approach, Pattison and Torrens pass a line across to Mole and start to take her in tow.

We sail on, feeling rather like Hornblower checking up on the convoy after a brush with French privateers. Up comes Tadpole, fairly bouncing over the waves, with Alexander sitting right out—and at times in the water—grinning hugely. He gives the thumbs-up signal, so we turn our attention to Badger, which is close to the shore in shallow water, with Wall and Johnson wading beside her.

They explain that their rudder is damaged and that they intend to walk her along nearer to the mouth of the Hamble, hop on board as soon as the wind is abaft the beam, and come home steering with an oar. This is clearly the right thing to do, so we return to the others, checking our way to keep pace with the heavily burdened Firefly and the Duckling. We sail along together, in the brilliant sunshine now, with the wind whipping the spray from the wave tops.

As we enter the river the tow is cast off, and Davidson takes Mole into sheltered water by Fairy’s slipway. As he and Northern step the mast and prepare to sail up to the club, we go back to see if Badger wants a tow. No—here she comes, running with the river under jib, with an oar out astern. We all come back to the hard, very wet but having enjoyed ourselves and put our seamanship to the test.”

The club at that time consisted of Munro, Sedgwick, Hayes, Liddell, Whitehead, Torrens, Davidson, Northern, Pattison, Alexander, Wall, Johnson, Wilson, Parrott, Jenson, Burkinshaw, Wright, and Rowe (the last six being Old Timers).

Bibliography: Appendix 5, Memories of Stanbridge Earls, Sailing 1962, by Douglas Home, History of Stanbridge Earls School.

Obituaries

Robin B. H. Grant-Sturgis (B) left Stanbridge in 1968 (at the end of the Spring term). He was a monitor and played 1st XV rugby, 1st XI hockey and was an estate worker.